Pier 54 in New York has a history that dates back to the city's first inhabitants. After being severely damaged in 2012 with the passage of Hurricane Sandy, Barry Diller and the Hudson River Park Trust institution worked to create solutions to reactivate it and return the space to the public.

The final resulting project, Little Island Park, became an urban oasis of almost 10,000 square meters, which is structured on 132 pillars and houses amphitheaters, and several species of trees and other vegetation, in addition to other attributes. With the architecture developed by Heatherwick Studio and landscaping by MNLA, the work presented numerous difficulties, which required great innovation and collaboration between many professionals. Arup, a global company that develops consulting and engineering projects, was involved in the project from the beginning. We spoke with David Farnsworth, Principal at Arup’s New York office & Project Director of Little Island, about the challenges and learning involved in this process:

Eduardo Souza (ArchDaily): Little Island project is innovative in many ways. What were the main challenges in designing the structural, MEP design and in the construction? For example, why did you decide to use precast concrete? Or, how could such a complex topography be built on pilotis?

David Farnsworth (Arup): Collaboration was essential on this project, where every design decision required changes to its global geometry. The architecture, landscape, structure, MEP systems, hardscape design, and drainage design were all linked. The complexity of resolving issues, from meeting ADA slope requirements to trees needing certain depths of soil, became clear very quickly. Due to the investment we made in parametric design, there was a smooth and collaborative workflow between architects and engineers on this project, which allowed us to automate the geometric generation of the complex pot surfaces.

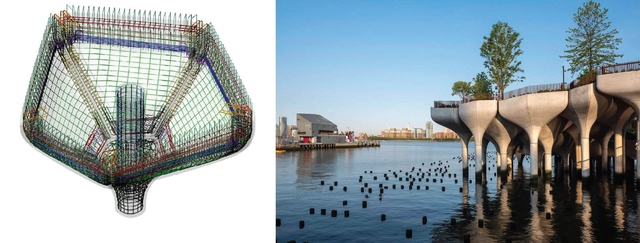

One of the big challenges for the project was: how can we achieve the design ambitions of a “floating” island with a level of repetition necessary to make precast economical? We settled on precast concrete for its durability, constructability, and economic feasibility when in a repetitive format. Hudson River Park also has a long history of building precast piers in the harsh Hudson River environment; utilizing prefabrication minimizes the amount of work over water. To achieve the level of repetition needed, we defined the pots using a tiling pattern based on the Cairo Pentagon shape, where the basic pot shape is repeated and rotated to look unique but is actually repeated on plan. We added a few variations on plan shape to form the edge of the pier, revealing a solution for the basic building blocks that could flex to meet the design requirements.

The undulating topography was also a key challenge for Little Island, and the precast is what fundamentally differentiates this pier from other more conventional marine structures. We took the basic Cairo Pentagon pot shape and made a few elevational variations so the pots could slope up in different directions. We ended up casting 132 pots out of 39 unique forms.

ES: What were the main innovations in this project? From design, manufacturing and construction? What served as a learning experience for other future Arup projects?

DF: The most notable aspect of our work was the benchmark structural approach we devised for this project, harnessing advanced 3D design and prefabrication techniques to achieve Little Island’s unique aesthetic while ensuring it optimized constructability. One of the key issues was finding the right construction partners — very early on in the process the design team, client, and CM team from Hunter Roberts met with many potential precast partners to convince them this could be built. We also broke the pots up into pieces that could be shipped via road to make sure the pool of potential bidders was not limited to suppliers based on the water. We found great partners in both Fort Miller and Weeks Marine, convincing them the best way to deliver this complex project was through digital fabrication.

As a design team, we blurred the conventional boundary between contractor and designers to deliver fully-detailed, direct-to-manufacture 3D models (created using parametric design software) for all of the pot precast components, rebar, connection fabrications, and sheet metal closure forms. This direct digital fabrication process ensured that the complex curved precast lined up and met the tolerances desired on site to make the pots look like monolithic elements with clean, consistent joints.

ES: On a project like this, should architecture, engineering, and other teams be aligned from the initial phases? How does this improve the outcome?

DF: A project like Little Island is only possible through collaboration among the design team, contractors, and fabricators. It was critical we worked with UK-based design firm Heatherwick Studio and New York-based design firms MNLA (Landscape Architect) and Standard Architects (Executive Architect) early on, and actively engaged the latest digital technologies such as parametric and automated design, 3D-model deliverables, and fabrications with CNC-milling of foams and laser cutting of steel plates. To this point, the whole design team also worked in a 3D environment to accurately understand elevation variation within the park and to mitigate potential clashes between trades.

ES: In addition to the topographical and vegetation we see in the photos, there is extensive infrastructure to support a wide variety of events, shows and concerts. Can you talk a little about this?

DF: Our integrated team of venue experts was tasked with developing a variety of soundscaping, acoustics, sightline, and seating strategies that optimize performance quality and user comfort while not distracting from the overall feel and quality of the park.

Working with Hudson River Park Trust, we sorted through a wide array of design and performance options, ranging from large-scale music shows to park-wide multimedia art installations, to accommodate world-class performers. The Arup SoundLab was used to simulate the acoustic experience for all three performance spaces at Little Island.

ES: Some say that learning to occupy the waters will be important for a future with higher ocean levels. What do you think of this and how can those of us in the construction industry work to mitigate it?

DF: Little Island was originally conceived of as a leaf floating on water, which is quite different from a typical pier design, and building the park in a harsh marine environment was always a present but welcome challenge. Rising sea levels was a key driver in the decision to make the park an island pier rather than a typical linear pier. By separating the pier from the esplanade, where the ground elevation is already set below the flood levels, we were able to elevate the main pier above rising flood levels and utilize the accessway bridges to gently slope up to the raised level. Our team of civil engineers also worked closely with MNLA and Arup’s structural team to develop an integrated stormwater management scheme that transforms Little Island into “one giant green roof.” A network of green infrastructure elements thoughtfully integrates into the park’s landscaping, making virtually the entire park impervious like a sponge. As soon as stormwater runoff is captured by one of these surface features, it begins to filter down through the pier structure’s substrata, which is designed to treat the water before gradually releasing it back into the Hudson River. This is one solution we found in effectively harnessing Little Island’s location on the water for advanced stormwater management.

ES: Is there anything else you would like to add?

DF: Little Island is a project that Arup has been working on since 2013 and one that harnesses the latest advances in digital design and fabrication technology.

The tools and processes were important to achieve the results we all can see on site today but the most critical ingredient to success was the collaborative effort between the client, design, and construction teams to solve problems and take the chances associated with doing something different and new.

The design and construction teams were able to deliver a project that retains the magic of the ambitious architectural vision that so captivated us all when we started.

Check out our curated Community of Professionals and find the right collaborator for your next project. If your company has been credited in any of the projects we published - we invite you to verify and edit your ArchDaily profile here. As always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us.